On Day 3 we got to sleep in a little later than we had the day before. Our hotel was already located near the site we were planning to visit, so we did not have to be on the bus until 9:30. Today we would be seeing the museums and temples at Agrigento. Known to the ancient Greeks as Akragas, the city was founded in 581 BC (as Thucydides tells us) and before long the city had grown to be very large and wealthy. Among other things, the people of this town raised crops and horses. As in many Greek cities, temples were built here not only to honor the gods but also as signs of the city’s riches. The more temples a city had, the wealthier it was. Here at Agrigento an impressive collection of at least seven temples (and possible as many as 20) was amassed, leaving the area with the nickname it still has today: “The Valley of the Temples.” Not to be confused with Egypt’s “Valley of the Kings,” where King Tut was buried.

We spent our morning visiting the nearby museum. The entrance to the museum looks out over the area where the ancient council would once have sat. Like many other cities in ancient Greece, Akragas was a democracy, and it was here that members of the assembly would meet to debate and cast their votes:

Once inside the museum we made our way to a large central room. This room houses an exhibit on the once-great Temple of Olympian Zeus. We would get to see the collapsed ruins of the temple in person later on. This was the largest temple in the city, and it was surrounded by several large stone giants who appeared to be holding up the roof. Here, with people left in the picture for scale, you can see one of the re-assembled giants standing over the room:

Notice how the legs are narrow near the feet. This was done so that the giant would appear to be proportionally correct when people were standing under it. Otherwise it would look like his body was all feet with a very small head. Even at this early time, the Greeks already understood perspective.

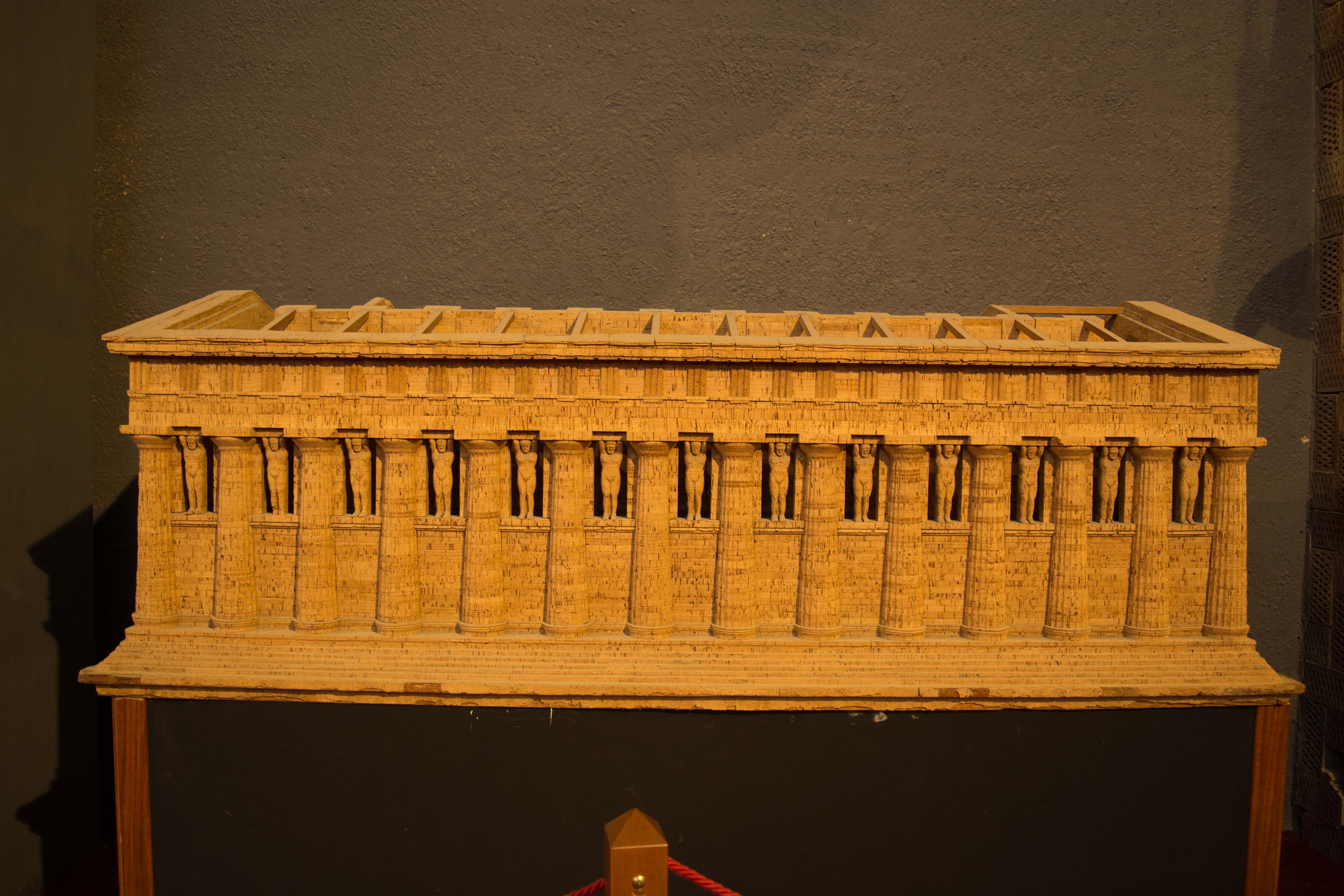

This model shows what the completed temple would have looked like:

In a glass case nearby, several clay figures which were once votive offerings are on display:

There are also some oil lamps:

And several lifelike stone busts:

This museum holds an impressive collection of ancient Greek pottery, including both red-figure vases and black-figure vases. Denise explained the process the Greeks used to make these. First the body of the vase would be formed out of clay. Sometimes this was done on a pottery wheel, and other times it was done in sections. The body of the vase would then be allowed to dry. Once it had reached the texture of leather the image could be applied.

The painter would use a brush to paint a thin layer of “slip” on the outside of the pot. This slip was a dark, thin-liquid clay, roughly the consistency of paint. In the case of an artistic image, the figures might first be drawn on the pot with a charcoal pencil and then filled-in with the slip. Once the slip was applied, the painter could use a sharp instrument to cut detailed lines into the image.

Then the pot would be fired in 3 successive stages. The first stage involved the pot being placed into a kiln with all of the vents open. This produced a very hot and oxygen-rich environment which turned both the pot and the slip a dark red. The second stage involved adding damp would and closing the vents. This produced a lot of smoke, driving oxygen out of the kiln. This turned both the slip and the pot a dark glossy black. The thin slip would become chemically sealed during this part of the process, so that it would not react with oxygen anymore. The third and final part of the process involved opening the vents to allow oxygen back into the kiln. Everything that was able to react with oxygen would turn back to the red color it had been during the first part of the process. But since the slip had been sealed during phase 2, it would stay black while the clay around it turned red. This left the familiar black figures on a red background, known as “black-figure” pottery. The final result looked like this:

In around the 6th century BC, painters in Athens came up with the idea to create a new style in which the slip was used to color in the background and the figures were left as plain clay. This was the artistic opposite of the earlier method. Once the same 3-part firing process was completed, the pot would have the appearance of red figures on a black background. This is known as “red-figure” pottery:

Here is another example:

The images on these pots were frequently images from Greek mythology, or depictions of events and practices from everyday life:

This piece has the familiar 3-legged symbol on it, which represents Sicily:

In another room nearby was a collection of Greek sarcophagi (coffins). This one has some familiar elements of a temple on the outside:

The inside is very plain:

This one, made for the funeral of a small child, is more elaborate. A scene from the child’s funeral decorates the outside:

There was also an image of the child riding in a chariot:

Once we had finished seeing the museum we headed outside to see some Hellenistic houses, built from 325 BC onward. This little residential neighborhood looks just as you might expect ancient ruins to look:

The houses and streets follow a familiar grid pattern, and continued to be used well into the Roman period.

Here we got to see some active excavations taking place. In the distance you can see the archaeologists working under a temporary structure that protects them from the sun:

I will not be able to post any pictures of the excavation itself, but it was quite an experience to be able to walk over there and watch them work!

Some of the already-excavated floors had elaborate mosaic patterns on them, including this circular one:

In this house, a doorstep and some drainage tile are visible:

This mosaic floor was even more elaborate:

We then proceeded up the hill to meet our local guide, and to see the temples that this area is famous for. Our first stop was the Temple of Hera. This temple was built around 450BC, and our guide told us that it aligns with the constellation of Delphi. This temple collapsed in an earthquake, so most of the pieces are scattered on the ground, but some columns are still standing upright:

The red color visible in the bottom left of this picture is fire damage, caused by the Carthaginian army. In 406 BC Carthage attacked Agrigento (then known as Akragas) and, after an 8-month siege, ransacked and burned the city.

Heading down the hill towards the next temple, we passed some Christian burials cut into the ancient city wall. These have semi-circular openings over top of them, and the body was placed in a hole beneath the opening:

These walls stretched a total of 6 miles around the ancient city, and were mentioned briefly by Virgil in his book “The Aeneid.”

Our next stop was the Temple of Concordia. This temple remains very well-preserved, and was built around 430BC.

The familiar elements of the columns, capitals, and roof are all here:

These arch-shaped openings in the interior were added in the 6th century AD, when Christians converted the temple into the church of Saints Peter and Paul. Some of the best-preserved Greek temples are those which were converted into churches, including one of the temples at Paestum:

Heading further down the hill, we passed some more Christian burials cut into the rock. These are very similar to the ones seen at Cuma during last year’s Pompeii trip:

The last temple we would visit was the Temple of Olympian Zeus, once the largest and grandest temple in Agrigento. This is where the giants, seen earlier in the museum, would have stood all around the exterior appearing to be holding up the roof. This temple, like the Temple of Hera, was destroyed by the Carthaginians in 406BC. It was further damaged by plundering and earthquakes over the years, and now only rubble remains. But the size of the remnants was nevertheless amazing. As we approached the ruins, this enormous quarter-capital made quite an impression:

Another capital, which we were able to walk up to and touch, made it very easy to appreciate the temple’s great size:

This section of the temple platform, with people nearby for scale, gives another idea of how massive this temple would have been:

The foundations of the temple, which run 20 feet deep, are also visible:

And one of the original giants, pieced back together, was visible here too:

Even the collapsed ruins are impressively high:

It was quite overwhelming to try to imagine what a sight the temple once was, towering high over the city and valley surrounding it.

After stopping at the nearby café for snacks and ice cream, we got back on the bus and made our way back to the hotel. During the evening we would be treated to a lecture from Lindsey Davis, the famous British author, who accompanied us on our tour. She has written a sizeable series of detective novels set in the Roman Empire. Although the novels are historical fiction, they are based in historical fact, and she explained to us this evening how she goes on tours to ancient sites such as this one to do research and develop ideas for her books. She also reads as much Roman history as she can get her hands on and visits museums quite often. If you get the chance to read any of her books, they are highly recommended!

That was the end of Day 3! In my next post I will cover Day 4, when we visited the ancient Roman villa of Piazza Armerina. This 3rd-century AD Roman house, with some of the most incredible mosaics I have ever seen, was a sight to behold! Check back soon!