Over the course of my first day on the trip I saw quite a few sites, and took more photos than on any other day of the tour. For that reason, I have decided to break the day into two parts to make it more manageable to read.

My trip to Berlin started with a long layover in Philadelphia. There aren’t many routes from the US to Berlin (most flights go into Frankfurt), so this was the only desirable option that took me directly to my destination city. Since I would be on the ground in Philly for so long, I decided to leave the airport and go see some of the historic sites there. I don’t normally leave the airport during a layover, but this on this particular trip I had plenty of time on my hands.

I took a cab from their airport to Independence Park, where my first stop was to see Independence Hall. This is, of course, the building where both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution were debated and signed:

I wanted to go inside, but that requires a timed-entry ticket and unfortunately they were completely sold out for the day by the time I arrived. So I made my way to Old City Hall, which is right next door and does not require a ticket:

Once inside I met a ranger who explained that this is where the US Supreme Court sat during the first few years of its existence. The court moved to Washington DC once everything was ready, but in the meantime several important cases were heard in this room. The most important of these was Chisolm v. Georgia, in which a private citizen attempted to sue the State of Georgia. Georgia claimed that, as a sovereign state, it was immune and therefore could not be sued. The court ruled against Georgia, allowing the lawsuit to proceed. Eventually this case would lead to the creation of the 11th Amendment (the first amendment to be passed outside of the Bill of Rights), which provides some protection for the States against lawsuits:

My next stop was the site of the First President’s House. Situated only about a block away from Independence Hall, this house saw many important events in early American history.

During the American Revolution, when Philadelphia fell to the British Army, General Howe set up his headquarters in this house. He would have stayed here during the same winter that George Washington and the Continental Army spent at Valley Forge. Once the British left Philadelphia, Benedict Arnold stayed here. He may have pondered his now-famous act of treason while sitting within these walls. After the war was over the house was damaged by a fire, and at that point it was offered as an investment opportunity to a wealthy local man named Robert Morris. More on him in just a minute.

The foundations are all that remain of the house today:

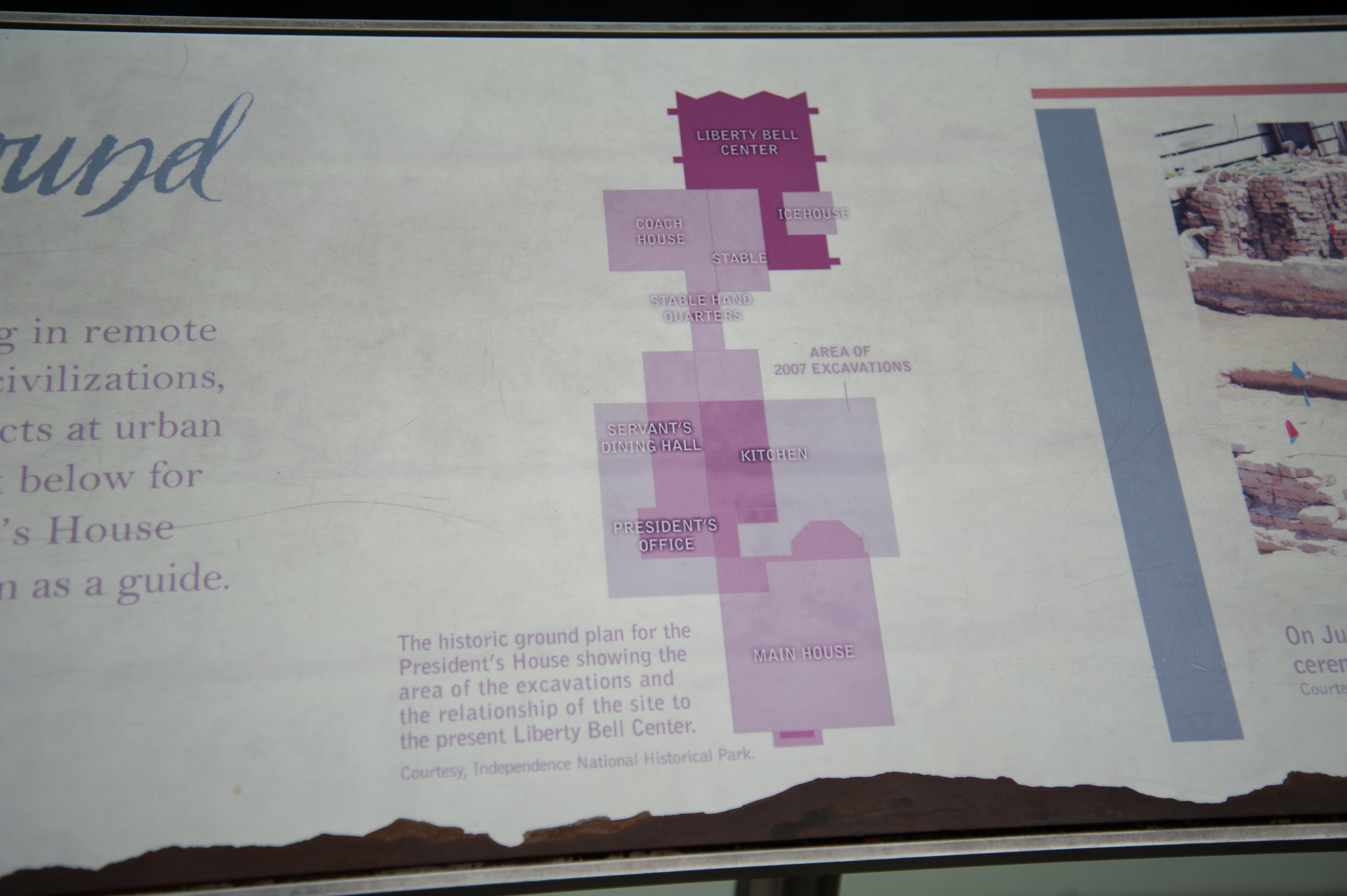

This plaque on the site shows what the layout of the house would have looked like:

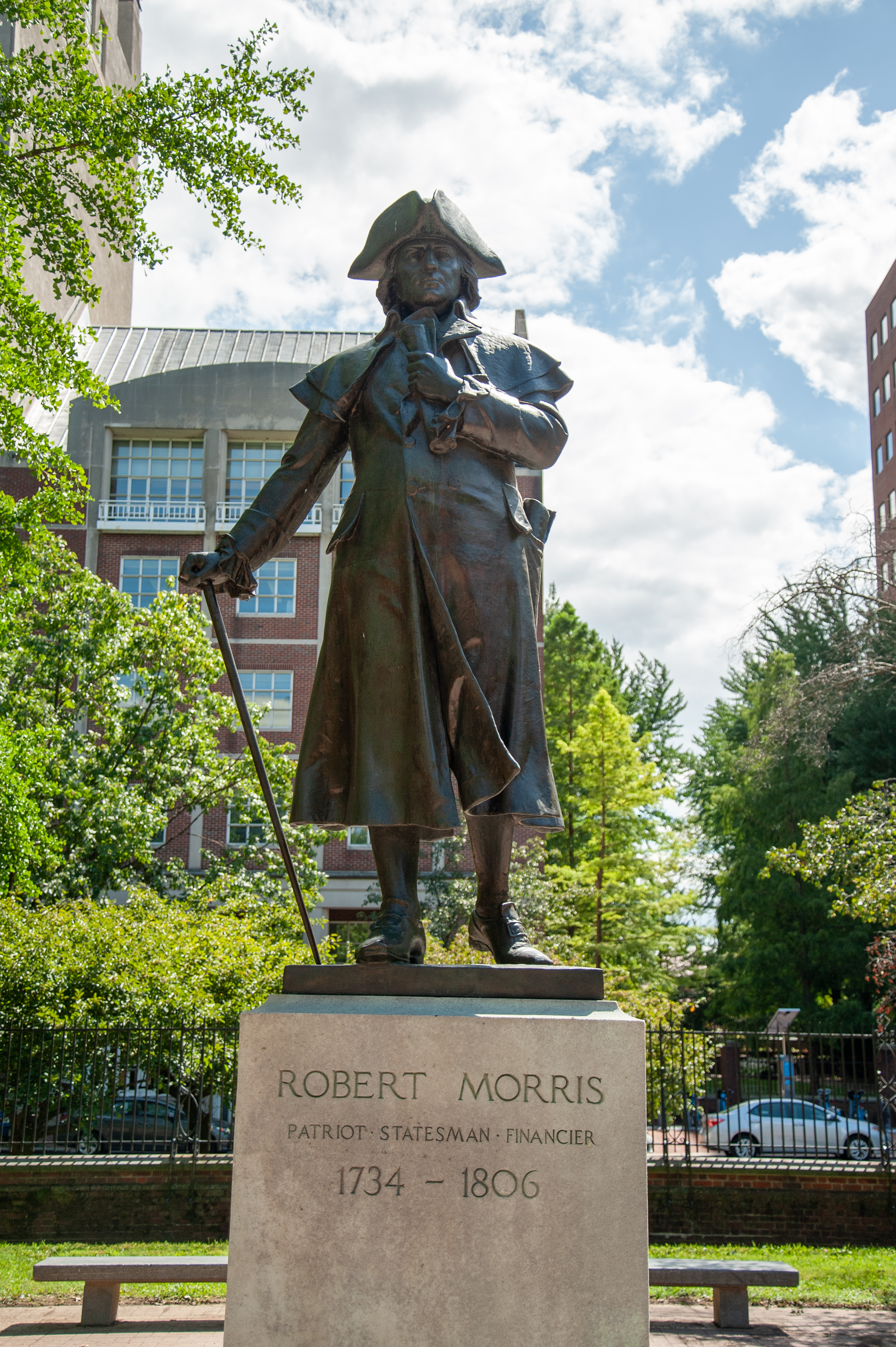

Robert Morris is my favorite Founding Father. As one of only two people to sign all three of America’s founding documents (Declaration of Independence, Constitution, and Bill of Rights) Morris’ influence was somewhat quiet and uncelebrated, yet benevolent and ever-present. His generosity and prudent financial skills were also instrumental in keeping Washington’s army supplied so that the Revolutionary War could be continued.

By the time of the Constitutional Convention, Morris had fully repaired and renovated the house and was living here. Since his friend George Washington had to travel to join the convention, Morris offered for Washington to stay at his house until the Convention was finished. Washington accepted the invitation. It was very exciting to stand on the site and consider the conversations that Morris and Washington might have had in these rooms during the evenings, once the day’s debates were over and the other delegates had gone home.

Once the Constitution was ratified, Robert Morris offered the house to be used as the President’s House while the new Capitol was being built in Washington DC. It thus served as America’s first “White House.” George Washington and John Adams both stayed here during their presidencies. John Adams eventually moved into the new White House in Washington DC, where every president since has spent their time in office.

Today the site hosts a very moving exhibit on slavery in early America, and this large stone memorializes the names of some of the slaves who were kept here:

My next stop was to see the Liberty Bell. The entrance to Liberty Bell Center is right next to the First President’s House. It took a little while to file through the line and to get through security, but eventually I made my way inside:

Finally, my last stop was to see the statue of Robert Morris located here at Independence Park. As I mentioned before, Robert Morris is my favorite founder, so while this part of the trip may not have ranked high on the list for many people, it was important for me. It took a longer walk than I expected, and a little help from Google, but eventually I found it:

At this point it was time to head back to the airport and catch my long overnight flight to Berlin.

My flight landed at Tegel Airport in Berlin right on time, and once I had cleared passport control, customs, and immigration I headed for the bus stop located just outside the terminal building. Berlin has a series of trains, trams, and busses that can all be used with a single ticket, so first I would need to stop at a booth and purchase one of these. I bought a 7-day ticket, which allowed me to use all of the available options for the entire week.

Ticket in hand, I took the bus to the subway station (called the U-Bahn in Berlin) and rode the train all the way to Friedrichstraße (meaning Frederick Street, pronounced “Free-Derek-Strahhzuh”), and walked from there to the hotel. Unfortunately my room was not quite ready yet, so I dropped off most of my luggage and headed for a museum. I had plans to visit Alexanderhaus (also known as the House by the Lake) at 3:00, but first I had several more hours to fill.

I decided to pay a visit to the DDR museum, which houses exhibits about day-to-day life in the communist East Germany (known at the time as the Deutsche Demokratische Republik, or DDR). The museum is divided into several sections, with exhibits on employment and education, cars, typical housing arrangements, state surveillance, and communist-era prisons.

The first exhibit I saw was this small model of the Berlin Wall. Here it is seen from the West side, which was the free side. Notice that people on the West side are able to walk right up to the wall, and as a result there is plenty of graffiti on it:

This side of the wall is viewed from the East side, which was the communist side. Notice that here there are lights, guard towers, barbed wire fences, and a wide “death strip” where guards waited to shoot anyone trying to cross:

Another exhibit demonstrated life in a typical East German tower apartment. After emerging from a simulated elevator, guests then stepped out into the hallway of the apartment:

The apartment had simulated windows, where you could look out over the streets and watch East German cars (Trabants) driving around in the city below. Notice the other tall but drab East German apartment buildings scattered around. The architecture on the communist side of the wall was not very impressive at all:

The next room was a demonstration of a typical kitchen. The decorations were outdated (correct for the time), but the appliances were all familiar:

Next to the kitchen was the living room, with a television and entertainment center facing the couch:

German-language magazines sat in the rack next to the telephone:

The entertainment center had many hidden compartments which showcased various aspects of daily life in communist East Germany. This one exhibited a typical household liquor collection:

At the top was a collection of family photo albums:

Elsewhere in the museum was a mock-up of a typical East German interrogation room. Here the Stasi (communist secret police) would try to extract information from citizens who had been detained:

A common Stasi tactic in these situations would be to ask the person, “Do you know why we invited you here for this little chat?” If the person answered, this would be taken as an admission of guilt. If they did not, the Stasi agent would leave the room, saying, “That’s OK. We have plenty of time.” The detainee would then be left without food, water, or contact with the outside world, while they waited for the interrogator to return.

Next to the interrogation room was an example of a typical East German prison cell:

And next to this was an example of a hidden surveillance station. The secret police would have had these hidden away in buildings all over the city in order to covertly gather data on the population:

At this point it was time for me to head back to the train station and start making my way to Alexanderhaus. This is a small family home on the outskirts of Berlin which was made famous by Thomas Harding’s international bestseller, “The House by the Lake.” Check back soon for Part 2!